![]() What news did the Star-Telegram proclaim unto its readers on December 24, 1920?

What news did the Star-Telegram proclaim unto its readers on December 24, 1920?

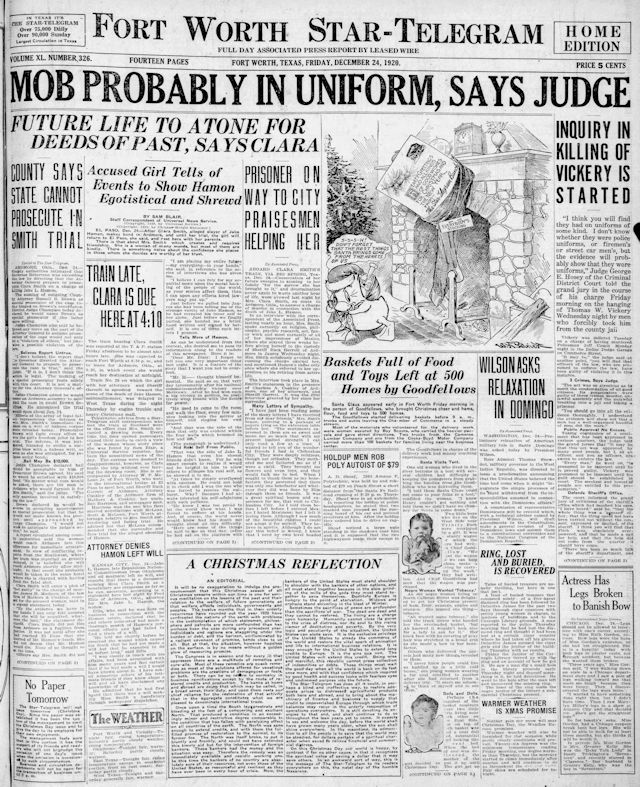

The banner headline on Christmas Eve a century ago held no “good tidings of great joy”: “Mob Probably in Uniform, Says Judge.” Tom Vickery had killed Fort Worth police officer Jeff Couch and had been lynched by a mob whose members reportedly wore uniforms. Some members of mob may have been members of the Ku Klux Klan and/or the Fort Worth police department. Vickery’s murder was the first of Fort Worth’s two Christmas lynchings at Hangman’s Tree.

The banner headline on Christmas Eve a century ago held no “good tidings of great joy”: “Mob Probably in Uniform, Says Judge.” Tom Vickery had killed Fort Worth police officer Jeff Couch and had been lynched by a mob whose members reportedly wore uniforms. Some members of mob may have been members of the Ku Klux Klan and/or the Fort Worth police department. Vickery’s murder was the first of Fort Worth’s two Christmas lynchings at Hangman’s Tree.

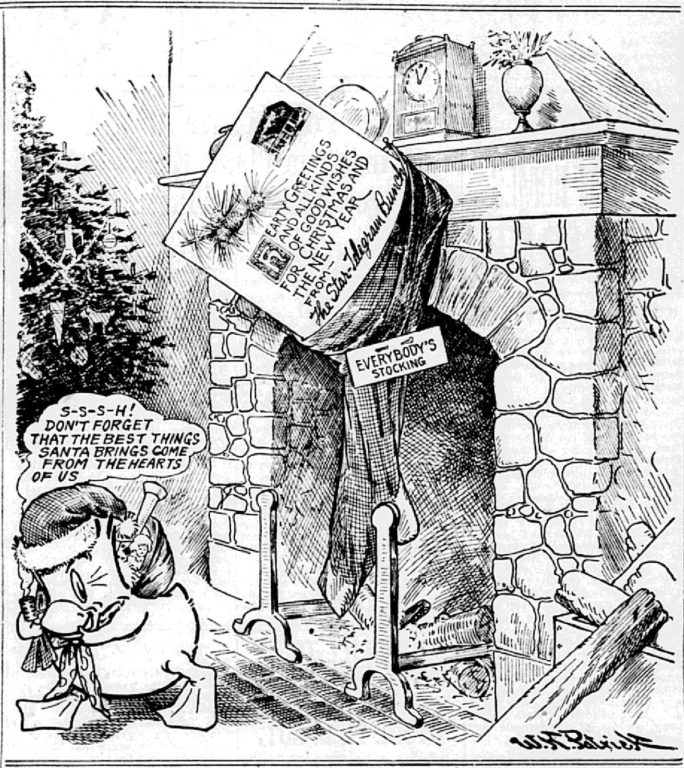

On a brighter note, the Star-Telegram’s front-page cartoon by William K. Patrick reminded readers: “Don’t forget that the best things Santa brings come from the hearts of us.”

On a brighter note, the Star-Telegram’s front-page cartoon by William K. Patrick reminded readers: “Don’t forget that the best things Santa brings come from the hearts of us.”

And indeed Cowtowners opened their hearts to the less fortunate. For example, the Star-Telegram’s Goodfellow Fund, begun in 1912, collected and distributed food and toys of hundreds of needy families.

And indeed Cowtowners opened their hearts to the less fortunate. For example, the Star-Telegram’s Goodfellow Fund, begun in 1912, collected and distributed food and toys of hundreds of needy families.

Sanger’s department store gave newsies caps with ear muffs.

Sanger’s department store gave newsies caps with ear muffs.

Tire Service Inc. offered people free use of its service cars (cars used to deliver passengers or freight) to take gifts to the poor.

Tire Service Inc. offered people free use of its service cars (cars used to deliver passengers or freight) to take gifts to the poor.

Not overlooked were veterans, aged Masons, “inmates” of Volunteers of America’s two maternity facilities, and Fort Worth Baby Hospital.

But Santa would bring no white Christmas to Cowtown in 1920. To find snow you’d have to travel 65 miles to Sherman or 150 miles to Knox City.

But Santa would bring no white Christmas to Cowtown in 1920. To find snow you’d have to travel 65 miles to Sherman or 150 miles to Knox City.

Members of TCU’s Horned Frog football team, including “Dutch” Meyer, were spending Christmas at their homes before playing the Praying Colonels of Centre College of Danville, Kentucky at Panther Park on New Year’s Day 1921. (The Colonels’ prayers would be answered: They would defeat the Frogs 63-7 in the first—and only—Fort Worth Classic college football bowl.)

Members of TCU’s Horned Frog football team, including “Dutch” Meyer, were spending Christmas at their homes before playing the Praying Colonels of Centre College of Danville, Kentucky at Panther Park on New Year’s Day 1921. (The Colonels’ prayers would be answered: They would defeat the Frogs 63-7 in the first—and only—Fort Worth Classic college football bowl.)

The Star-Telegram reported news from the Stop 6 (named for the stop on the interurban at today’s Rand Street), Sycamore Heights, and Polytechnic communities east of town before those communities were annexed.

The Star-Telegram reported news from the Stop 6 (named for the stop on the interurban at today’s Rand Street), Sycamore Heights, and Polytechnic communities east of town before those communities were annexed.

Department stores such as Stripling’s wished their customers “a merrie yuletide & happiness.”

Department stores such as Stripling’s wished their customers “a merrie yuletide & happiness.”

Season’s greetings came from Monnig’s at “1300-2-4-6-8-10 Main St.” And Fakes offered a selection of eighty-five-cent “double-face” Christmas records to be played on its Victrola and Columbia “talking machines.”

Season’s greetings came from Monnig’s at “1300-2-4-6-8-10 Main St.” And Fakes offered a selection of eighty-five-cent “double-face” Christmas records to be played on its Victrola and Columbia “talking machines.”

Meanwhile at the courthouse, the clerk in charge of issuing marriage licenses, the aptly named Lorena Truelove, reported a decrease in customers compared with the previous Christmas Eve.

Meanwhile at the courthouse, the clerk in charge of issuing marriage licenses, the aptly named Lorena Truelove, reported a decrease in customers compared with the previous Christmas Eve.

And what about couples who had married? In the “For Women and the Home” section of the newspaper, syndicated columnist Adele Garrison advised wives about “holding a husband.”

And what about couples who had married? In the “For Women and the Home” section of the newspaper, syndicated columnist Adele Garrison advised wives about “holding a husband.”

Perhaps a box of Pangburn’s “deliciously blended, rare-flavored” chocolates would keep the shiver in Cupid’s quiver.

Perhaps a box of Pangburn’s “deliciously blended, rare-flavored” chocolates would keep the shiver in Cupid’s quiver.

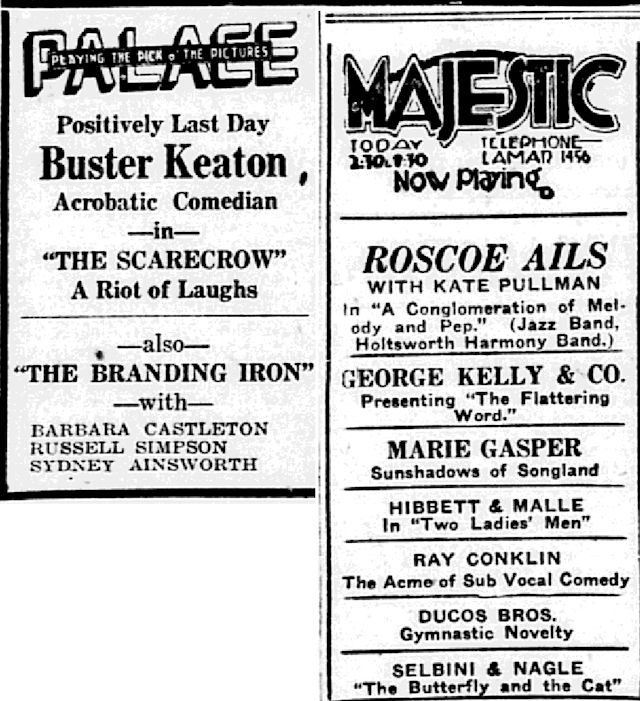

Downtown the Palace, the first of Show Row’s three theaters, was one year old in 1920. The Majestic Theater was still presenting live entertainment.

Downtown the Palace, the first of Show Row’s three theaters, was one year old in 1920. The Majestic Theater was still presenting live entertainment.

By Christmas Eve 1920 national prohibition had been in effect eleven months. The general counsel of the Antisaloon League predicted a shortage of Christmas spirits because consumption and enforcement had diminished the supply of alcohol. Nonetheless, stills proliferated, including in the basement of at least one church.

By Christmas Eve 1920 national prohibition had been in effect eleven months. The general counsel of the Antisaloon League predicted a shortage of Christmas spirits because consumption and enforcement had diminished the supply of alcohol. Nonetheless, stills proliferated, including in the basement of at least one church.

On the other hand, Prohibition did not extend to automobiles, which could guzzle all they wanted. Fort Worth Auto Supply Company sold alcohol to be used as antifreeze. And because the interior of the soberest of automobiles could be cold, wet, and drafty, the company also sold lap ropes, fur coats, and gloves.

On the other hand, Prohibition did not extend to automobiles, which could guzzle all they wanted. Fort Worth Auto Supply Company sold alcohol to be used as antifreeze. And because the interior of the soberest of automobiles could be cold, wet, and drafty, the company also sold lap ropes, fur coats, and gloves.

Prohibition also did not prohibit patent medicines that contained alcohol. For example, the holiday reveler who was sick of Prohibition could get well quick with the “splendid tonic” Pepto-Mangan, which was 16 percent alcohol. Likewise, the ad for Hood’s Sarsaparilla lists several of that tonic’s ingredients but omits one: alcohol (18 percent).

Prohibition also did not prohibit patent medicines that contained alcohol. For example, the holiday reveler who was sick of Prohibition could get well quick with the “splendid tonic” Pepto-Mangan, which was 16 percent alcohol. Likewise, the ad for Hood’s Sarsaparilla lists several of that tonic’s ingredients but omits one: alcohol (18 percent).

As the Roaring Twenties ended their first year, in addition to the ubiquitous Ford, other automobile brands included Hupmobile, Chandler, Haynes, Franklin, Sayers, Hudson, Chalmers, and Scripps-Booth—all now consigned to the salvage yard of history. For example, the Haynes Automobile Company began production in 1905, was bankrupt by 1924, and out of business by 1925. ($750 would be $9,800 today.)

As the Roaring Twenties ended their first year, in addition to the ubiquitous Ford, other automobile brands included Hupmobile, Chandler, Haynes, Franklin, Sayers, Hudson, Chalmers, and Scripps-Booth—all now consigned to the salvage yard of history. For example, the Haynes Automobile Company began production in 1905, was bankrupt by 1924, and out of business by 1925. ($750 would be $9,800 today.)

Lastly, the P. H. Hanes Knitting Company suggested this gift: “union suit” underwear.

Lastly, the P. H. Hanes Knitting Company suggested this gift: “union suit” underwear.

Merry Christmas Eve, y’all. If you go out for a drive tonight to look at the Christmas lights, there’s no snow in the forecast (just as a century ago), but it will be chilly. If you take your Haynes, take your Hanes.

Washer Brothers

Washer Brothers Haltom’s

Haltom’s Sanger’s

Sanger’s